UA Tree-Ring Research Helps Analyze Droughts in Mongolia

Future droughts could be as bad as the devastating 2000-2010 drought, but likely no worse, according to a team that included a UA dendrochronologist.

The extreme wet and dry periods Mongolia has experienced in the late 20th and early 21st centuries are rare but not unprecedented and future droughts may be no worse, according to an international research team that includes a University of Arizona scientist.

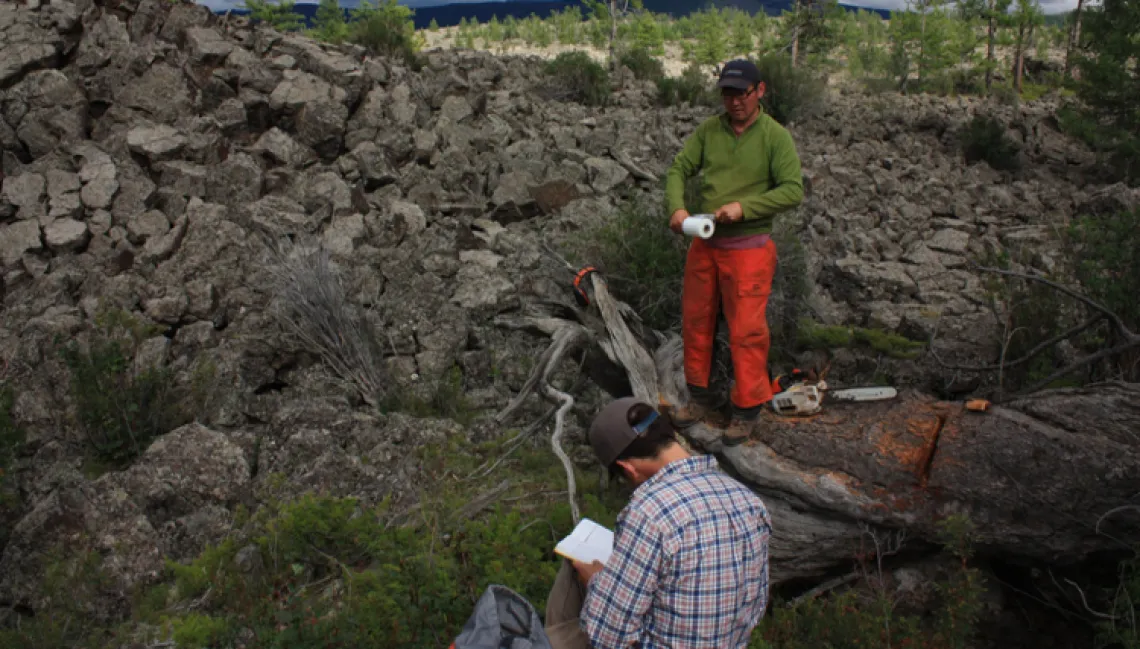

The research team developed a climate record stretching 2,060 years into Mongolia's past by using the natural archive of weather conditions stored in the annual rings of Siberian pines. The 10 researchers then combined that information on past climate with computer models that can project future regional climate.

The most recent extended drought in Mongolia lasted from 2000 to 2010 and resulted in major livestock die-offs and a massive migration of nomadic herders to the capital city.

"We were able to quantify how unusual this drought was," said co-author Kevin J. Anchukaitis, an associate professor in the UA School of Geography and Development. "The drought was not unprecedented, but it has a 900-year return interval. It’s a once-in-a-millennium drought."

Finding that future droughts would likely be no worse than those of the past was a surprise, said Anchukaitis, who led the modeling team. In other semi-arid regions of the world that he has studied, such as California and the Mediterranean, global warming already has changed precipitation and temperature patterns and thereby increased the risk of long-term drought.

Mongolia, a landlocked country in central Asia, has long, cold winters and short summers. Much of the country is cold, semi-arid grasslands that resemble eastern Montana.

Lead author Amy Hessl of West Virginia University said, "You would expect, based on everything we've been thinking about and reading as climate scientists, that elevated temperatures are going to lead to more severe droughts in semi-arid regions. But the models did not project increased frequency or severity of droughts."

The timing of the rainy season is the likely cause, the researchers said. Mongolia's rainy season is in the summer, the warmer time of the year, whereas California and the Mediterranean have winter rains and dry summers. As global temperatures increase, continental regions with summer rains may get more precipitation, offsetting the effects on plants of higher temperatures.

The team's research paper, "Past and Future Drought in Mongolia," was published online in Science Advances. National Geographic and the National Science Foundation funded the research.

Anchukaitis, who also has appointments in geosciences and in the UA Laboratory of Tree-Ring Research, is interested in how past and current civilizations dealt with drought and climate variability. This new research is an outgrowth of previous research he, Hessl and their colleagues conducted to figure out how past climate influenced the Mongol civilization.

Anchukaitis and his colleagues used their tree-ring record of past climate in Mongolia to reconstruct what the annual Palmer Drought Severity Index, or PDSI, would have been going back in time 2,060 years. The PDSI combines both temperature and precipitation to get a measure of soil moisture, one measure of how water-stressed a plant would be.

He and his colleagues combined the reconstruction of past annual PDSI measures with a set of climate model simulations called the Community Earth System Model to understand what influenced the Mongolian droughts for the period from 850 to 2100.

The model incorporates information about past solar variability, volcanic eruptions, land use changes and carbon dioxide emissions. For projections to the end of the 21st century, the model uses the future emissions scenario called RCP 8.5, in which the rate of emissions of greenhouse gases continues to increase.

Even with the highest level of greenhouse gas emissions and rising global temperatures, the model simulations indicate that future droughts in Mongolia would be no more severe than those of the past.

"There's a tug of war between trends toward increased rainfall and more evaporative demand because of hotter temperatures. There's uncertainty about which will win this tug of war," Anchukaitis said.

"The simulations say that Mongolia dries between now and about 2050 because of higher temperatures, but then it turns around because of the increase in precipitation," he said.

Many people in Mongolia are nomadic pastoralists. They are particularly affected by the vagaries of weather and climate, because the combination of winter and summer temperatures plus rainfall controls the number of cattle the grassland can support.

"What to me stands out is this deep uncertainty about the future, particularly when you have a society that is so vulnerable to climate variability," he said, adding that uncertainty makes it hard to plan for coping with future climate change.

Anchukaitis said one of his next steps is translating the team's estimates of future soil moisture into estimates of the future productivity of Mongolia's grasslands.

Hessl's and Anchukaitis' coauthors on the paper, "Past and Future Drought in Mongolia," are Casey Jelsema of West Virginia University in Morgantown; Benjamin Cook of Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, Palisades, New York, and NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies, New York City; Oyunsanaa Byambasuren of the National University of Mongolia, Ulaanbaatar; Caroline Leland of Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory; Baatarbileg Nachin of the National University of Mongolia; Neil Pederson of Harvard University; Hanqin Tian of Auburn University, Alabama; and Laia Andreu Hayles of Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory